Man & Elephant, a 4500-year history!

In order to shed more light on our intellectual approach, here are some extracts from a veterinary thesis published in 2009 by Dr Florence Labatut, to help you discover the strictly historical aspect of the human-elephant relationship, which seems to be even older than the human-horse relationship!

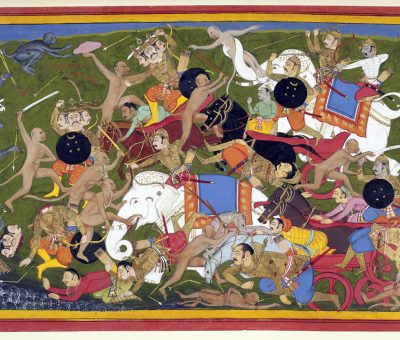

‘The history of south-east Asia, from India to Indonesia, has always been linked to that of elephants. The first written traces of domestication (4500 BC) can be found in the Indus Valley in the paintings in the ruins of Mohenjo-Daro, showing war elephants on a battlefield. However, it is reasonable to think that the domestication of the animal goes back even further, given the animal’s presence on the continent and the numerous domestications in different countries and ethnic groups. It is estimated that domestication began between the 9th and 7th centuries BC. At present, the Indian origin of the first domestications seems to be recognised, and is the most well documented. Traces of domestication can be found in ancient literature: the Vedas (1500-1000 BC) and the Rig-Vedas (1200 BC) and the Upanishads (900-500 BC) deal with the capture and training of elephants and describe elephant domestication as a highly refined practice.

The use of elephants throughout history :

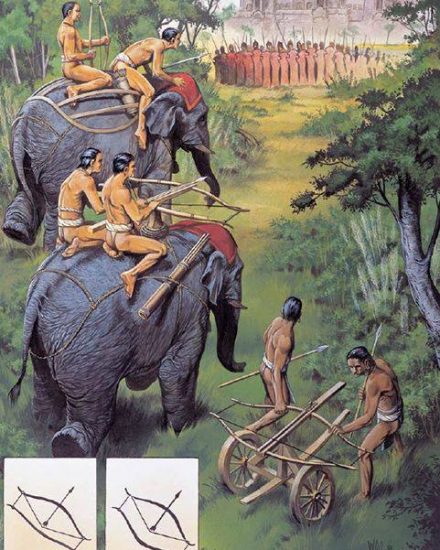

War elephants

The main advantage of elephants is their psychological impact: they are frightening because of their size, especially for people in the West who are not familiar with them. What’s more, in order to protect them while at the same time increasing their devastation, the Indians have taken to dressing them in combat gear. They wear leather carapaces and their tusks are fitted with metal spikes. Sometimes they wear a huge bell around their necks to frighten their opponents and their horses. Some elephants are even completely covered in iron plates and, to prevent their hocks being severed by the enemy, their limbs are protected by leather or metal rings. In addition to their armour, elephants were used as mounts for wooden turrets to transport and protect numerous archers and the warlord. Moreover, elephants were frequently aroused before entering the battlefield by arak alcohol and some historians assume that the use of elephants in musth was encouraged. A Tamil poem describes elephants on the battlefield as an animal ‘as gigantic as a mountain, whose roars resemble the roar of the sea and who, his temples flooded with musth, and swift as a gust of wind, is so formidable that death itself could learn from him the art of murder’.

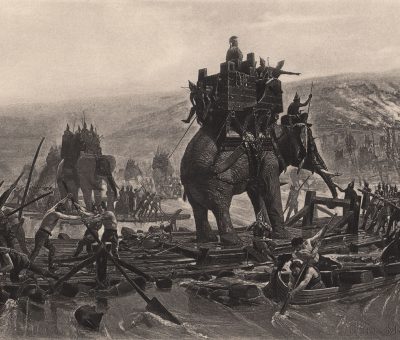

In the 4th century BC, the kings of the Ganges valley owned more than 5,000 war elephants. The elephant acquired great importance, which was reflected in the laws of the time, which required elephant forests to be left uncultivated and condemned anyone who killed an animal to death. The elephant was an indispensable weapon. Alexander the Great was the first to observe them on the battlefield. During his second attempt to conquer the Persian Empire, after crossing the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, he fought Darius III at Gaugamela (331 BC), who had an army of 250,000 men and 15 elephants (although the latter were not used); Alexander was victorious. It wasn’t until Alexander the Great fought Poros in 323 BC after crossing the Indus that he was confronted with 200 pachyderms on the battlefield. Alexander won, but realized the value of these animals during the confrontation. And so began the military era of elephants across the world.

In the 2nd century BC, elephants were introduced into the armies of the Eastern Mediterranean. These were probably Mediterranean elephants, a breed that has now disappeared. For decades, the great warlords used elephants. Hannibal (247-183 BC) was nicknamed the ‘one-eyed chief riding an elephant’. Their vital importance was particularly apparent during the 300-year war between Burma and Thailand, which brought together up to 20,000 elephants in the 18th century and from which Thailand emerged victorious after the Battle of Ayutthaya in 1767. Throughout the conflict, in Burma and into the 19th century, elephants were trained to capture the enemy with their trunks and kill them outright; they were also taught to march in line and give the military salute. However, their use on the battlefield is gradually being phased out, as elephants are fearful and easily vulnerable (trunk and hock sections). A frightened elephant is more harmful to its camp than it is to the enemy. Elephants flee in the face of fire, piglet cries, stone-throwing or when wounded. During one battle, for example, the Hegirians smeared pitch on pigs and set them on fire. The pigs let out high-pitched cries that frightened the elephants, but they responded by getting the elephants used to the presence of the pigs. In 46 BC, the Pompeians tried in vain to accustom the animal to receiving stones, and during the next battle, the elephants once again gave in to panic and ravaged their camp.

The devastation caused by the elephants in their own camp prompted the mahouts to find a solution to stop the frightened elephants. Titus Live illustrates this in his ‘History of Rome’ about Hasdrubal in 228 BC by explaining that: ‘A very large number of elephants were killed, not by the enemy, but by their own mahout. They were equipped with a carpenter’s chisel and a mallet, and when the beasts went mad and turned on their own side, the mahout used the mallet to drive the chisel between the animal’s ears, at the junction of the head and neck. It was the fastest method ever discovered for killing these gigantic animals. Hasdrubal was the first to introduce this method’.

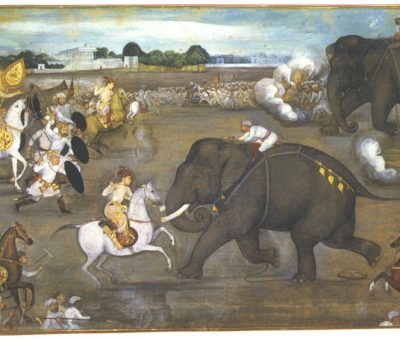

The invention of firearms put a definitive end to the use of elephants as weapons on the battlefield. In the 17th century, François Bernier wrote: ‘Since firearms have been used in armies, elephants are almost useless. It is true that some of these brave men brought to the island of Ceylon are not so timid, but this is only after they have been accustomed to them for years, firing muskets at them every day and throwing paper firecrackers between their legs’.

From then on, elephants served new military functions as pack animals and means of transport for armies on the march. They help to clear paths through the jungle, removing obstacles and opening up space. They can carry precious equipment and act as guides for troops, pointing out the best ways forward in often hostile and steep terrain. They could also be used to cross rivers on their backs and carry materials for the construction of bridges or roads, which were later used as passageways for troops. The new functions of elephants also have their limits. An elephant carries a maximum of 400 kg on its back and eats around 250 kg of food a day. Transporting their food was a major constraint and, over the centuries, few armies kept their elephants in peacetime.

The last wartime use of elephants was during the Second World War, when the 5,400 elephants present in Burma played an important role in the battle between Great Britain and Japan for control of Burma. Elephants were used to build roads, bridges and boats, and to transport supplies, men and wounded. During the Viet Nam war, convoys of elephants were prime targets for American aircraft, particularly those using the famous Ho Chi Minh trail.

The number of elephants killed or slaughtered has never been known, but it can probably be estimated at tens of thousands, if not millions, over the last three millennia. All this undoubtedly contributed to the threat of extinction that hangs over the species today.

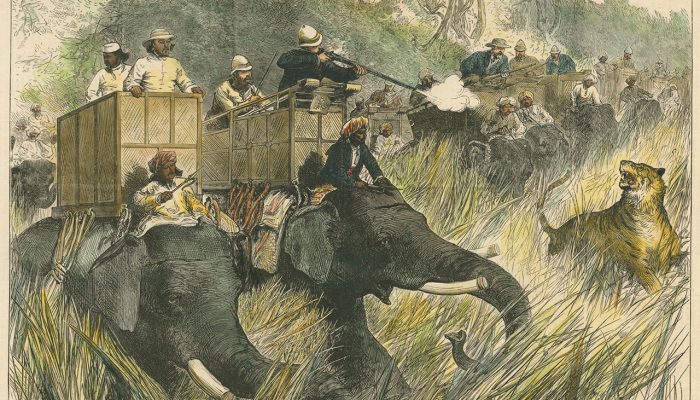

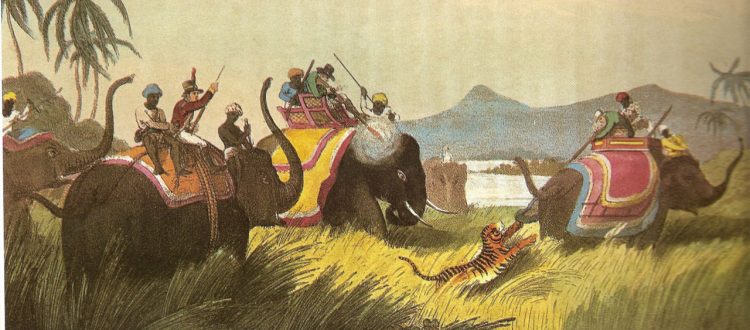

Hunting with elephants

However, the most common use of the hunting elephant was to hunt its own species. Throughout Asia, wild elephants were hunted on the back of domesticated elephants. This aspect will be developed in the second part.

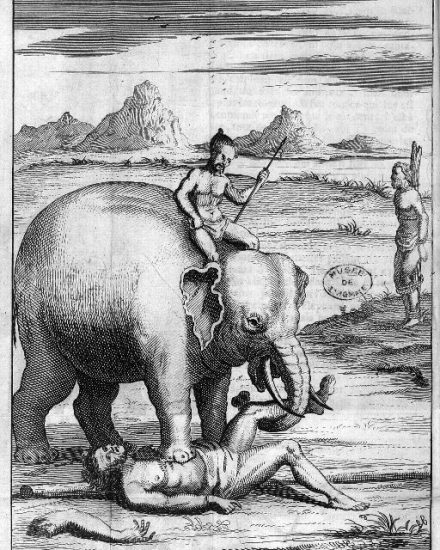

Elephant executioner

For centuries, elephants were used as executioners throughout Asia. It crushed the heads of those condemned to death.

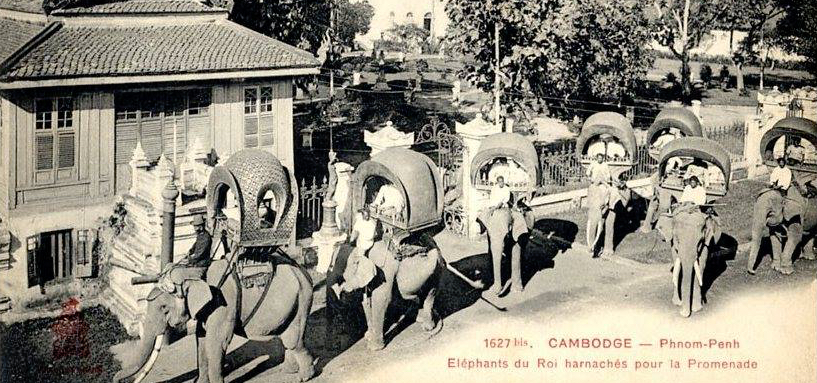

Parade elephants

Elephants are capable of kneeling and moving on their knees. In countries where etiquette dictates that people should bow or crouch before a person of higher rank than themselves, this rare feature of the animal kingdom has attracted a great deal of attention. In Asia, for example, elephants have been used as mounts for royalty, warriors and ceremonial purposes since ancient times. In the 19th century, Abbé J.A. Dubois, a missionary in Pondicherry, noted that ‘Indian princes and their officers consider this mount to be the only one suitable for their rank. They are always preceded by an elephant bearing their colours’. Royal elephantries existed in many countries, notably in India, Cambodia and Burma. In Burma, an animal was only worthy of entering the king’s service if it scrupulously met three hundred and fifteen criteria. Forty-two of these concerned general behaviour or physical faults considered to be absolutely prohibitive: the shape of the tusks, the way they grew, the way the elephant wagged its ears or tail, the texture of its skin, the way it fed or slept, and so on.

Elephants were and still are used to represent a country’s power, and at every official ceremony, they are used in royal processions as symbols of the country’s good health. In the past, during defeats or negotiations, elephants were used as bargaining chips. For example, at the end of the first century BC, Chadragupta Maurya, founder of the dynasty of the same name, made a gift of 500 elephants to Seleucos I, Alexander’s successor, in exchange for Greek possessions in Afghanistan. The elephant played, and still plays, a special role in Asian countries’.

Etat actuel

Les captures, les guerres, les nombreuses utilisations mais surtout la déforestation ont entrainé le déclin de l’espèce. Si hier l’Asie possédait des millions d’individus aujourd’hui elle n’en compte plus que quelques milliers répartis entre les sauvages et les domestiques.

Au Cambodge, véritable parent pauvre de l’Asie, on ne compte plus que 67 éléphants domestiques et environ 200 à 250 éléphants sauvages. Les éléphants travaillent principalement dans deux secteurs d’activité, le débardage et le tourisme et sont à court terme en voie de disparition. Néanmoins la population garde intact son attachement à l’animal qui conserve un symbolisme très fort.

La démarche d’AIRAVATA est de protéger à la fois l’animal, la forêt qui l’abrite et le nourrit ainsi que les traditions dont les Cambodgien l’ont entouré au fil de l’Histoire.